Why We Write - Part 2

Why We Write – Part Two

By Kirk Kandle

In Part One of this series, we took a very brief glance at the earliest writing technologies – the stylus, clay tablets, papyrus, paper and ink development. It took many thousands of years to develop the tools we needed to write with ease. Then along came electronics and in the blink of an eye, we seem to have abandoned pens and pencils in favor of digital devices. We’re all glued to our screens and no one seems to write letters anymore.

But how quickly we tire of the latest new shiny objects! Over just the past couple of decades, we’ve seen signs of “digital fatigue” due to way too much screen time and not enough of the human touch. It’s more than mere nostalgia. There seems to be a yearning for the old days when people took time to write thoughtful letters and drop them in the mail.

Today we see an emerging trend that has people searching for journal books and covers, paper planners, pens, inks and writing accessories that match their personal preferences. And they’re using all these tools to re-connect with the root of their particular communication styles and their unique voices in a way that digital devices simply cannot.

I’ve been an enthusiastic writer all my life. A ninth grade English teacher named Emily Keeling made me love the way words come together. Writing became my passion long before it became my choice as a profession. I take my time in writing, much to the disdain of assignment editors. I agree with the recently departed Kentucky writer Ed McClanahan, who said, “Writing is like performing brain surgery on yourself. It’s not something you want to hurry with.”

So, why do we write?

I asked Google this question and received about 2.5 Billion results. Clearly, it’s a topic that is very personal. There is no right or wrong answer. Why did those first ancient communicators take the time and effort to sharpen a stick and make marks in wet clay? What was so important that they had to make that idea permanent? What were they sharing with their friends and associates?

Archaeologists now understand a lot of the earliest clay tablets from the Middle East. At first, they were mostly used for accounting of crops and animals and other wealth. But soon, tablets were created to show maps of the known world, stories of mythical beasts and great heroes. So, you see, the more things change, the more they stay the same. Just like the ancient Sumerians, we use our language and math for accounting, describing the world around us, and for writing fiction and nonfiction. Before long, the administrators of the temples were teaching kids to write. The students likely hated composition classes as much as kids do today.

Scribe’s gonna scribble

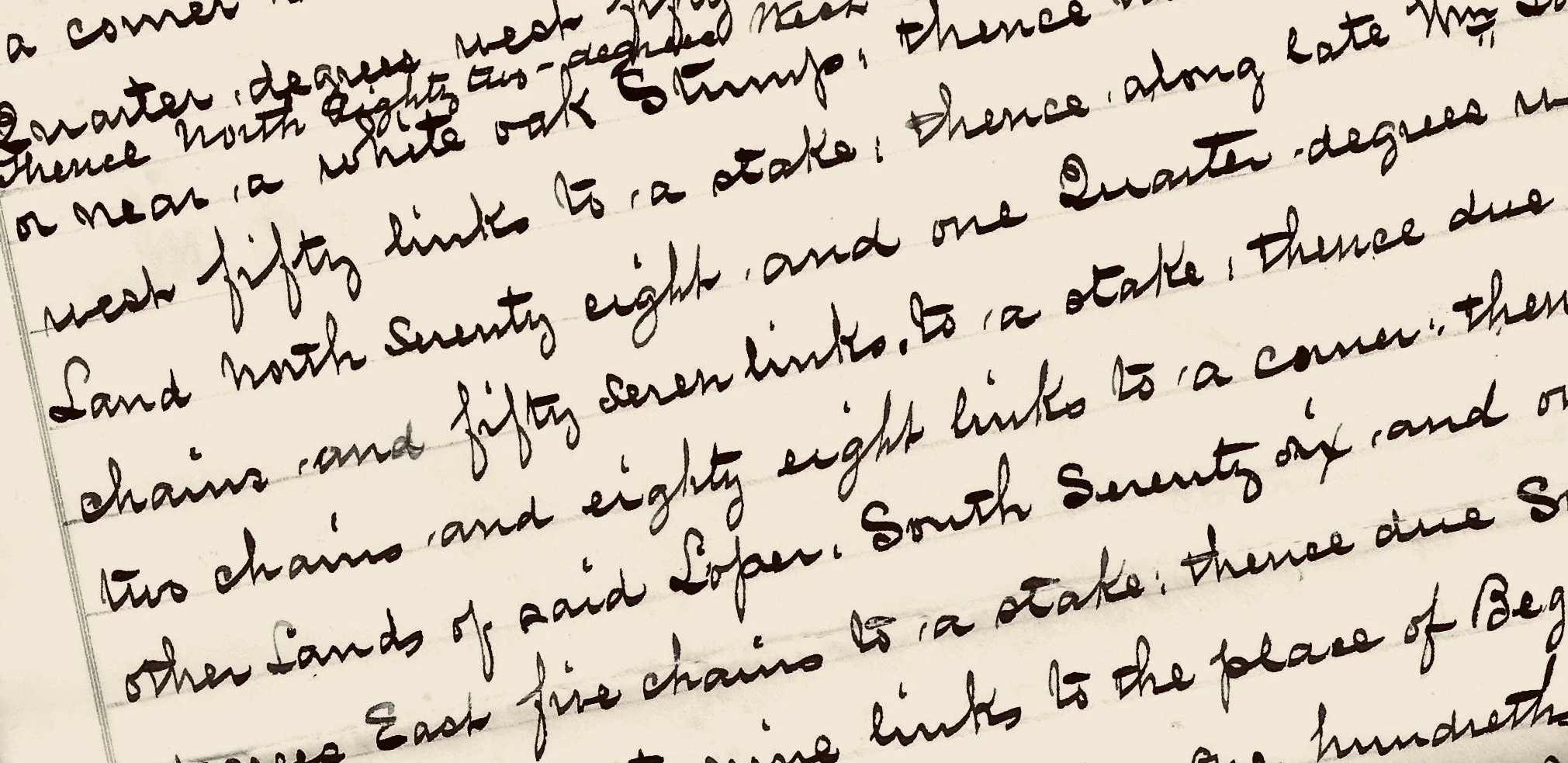

Hit fast forward from the days of cuneiform tablets, to the earliest documents in American history. They were not typeset. They were handwritten and signed by John Hancock, Thomas Jefferson, and by everyday folks in law offices, courthouses and business firms everywhere. Early on, before more modern printing techniques, scribes had to copy everything that needed to be distributed. They used pen and ink on fine paper. Even well into the early 20th Century, documents like land deeds were written with pen and ink by appropriately-named “copyists.”

This is an example of a deed copied and recorded in 1883, when my third-great grandfather bought a piece of land for the timber. The copyist was required to write this document at least three times – for the buyer, the seller and the recording office. Just a few years after this document was written, every courthouse and law office clerk would have Remmington, Underwood or Smith-Corona typewriters for banging out carbon copies.

Dear Diary

One of our main motivations for writing is reflection. Journaling a very popular pastime and has been for as long as human kind have been recording thoughts in any form. We look back on our lives and review achievements, struggles, disappointments, and our everyday activities. Keeping a journal or diary helps put life in perspective. Many writers never go back and read their journal entries. They can be intensely personal and meant never to be shared. But it’s the act of writing that satisfies a need to take stock of our lives in good times and bad.

For some writers, the need for self-expression is satisfied only when their thoughts are shared with a reader. Whether it’s through essay, poetry, fiction or nonfiction, some writers just need to be understood. Writing for them is the building of a relationship with a reader. It’s the writer who takes the first step in that relationship. It’s a risk the writer takes, often praying, ”O Lord, please don’t let me be misunderstood.”

It’s not for the money

In England, the Royal Society of Literature conducted a recent survey and found that most of the writers who responded make less than £10,000 per year. Most of the successful writers said they make more money from other occupations to support their writing.

I was a newspaper writer and freelancer for more than 40 years. I made a living and helped raise two children on the money I earned, but it was never the money that kept me going. I loved everything about the process of getting ink on paper. I was a fourth-generation printing press operator before getting a degree in journalism. I guess I still have ink in my veins.

No. It’s not about the money. More often than not, writing is its own reward. The act of writing gives one a form of mindfulness, an expression of gratitude, an avenue of escape and an opportunity to connect.

It depends on who you ask

Check with Google, and you’ll get nearly 2.5 billion results when you ask why we write. One blog cites three reasons. Another one points to 30 reasons. Some state the obvious. The primary reason for writing anything is to communicate with others, to stimulate interest or action from the reader.

I use writing to focus and better understand my experiences. I like to find common ground with others by expressing my own ideas and listening for the feedback. I’m a storyteller. And whether you know it or not, you are, too! Now the question is just how you will write your best stories?

NEXT: Why We Write - Part 3 explores how to equip yourself for the writing journey ahead. What tools will you use to make the writing experience more productive and more worthwhile. From pencils and pens to the latest phones, tablets and computers, the tools at our disposal have never been better or more numerous. The challenge is to pick one and start.